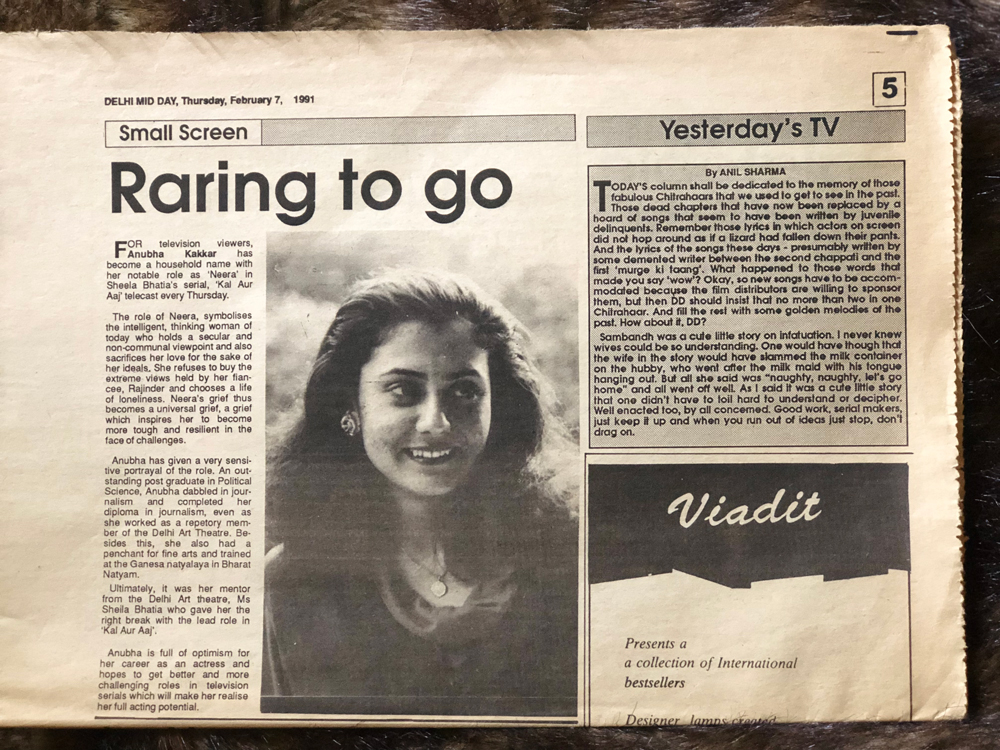

The professor said during the first class that he was very open to alternative writing styles and in his class, an essay didn’t have to follow the required academic format of other classes. I’d heard this kind of openness to alternative ideas rhetoric before but in reality, university is university, it’s all about academic form, and writing, and structure, so I didn’t have much faith in his statement that he was open to alternative writing styles. I decided to test him.

I drew a line across the horizon of some legal-size sheets of paper and in the top half, I wrote a book review of Margaret Atwood’s dystopia novel, The Handmaid’s Tale, and in the bottom half, I wrote an informative essay about infertility treatments and surrogate mothers and sex-selective abortion.

I’d taken a feminism course in reproduction the previous semester and I was still reeling from all the male opinions of what women should be allowed to do with their own bodies. The professor asked to see me after class.

“This is pretty unusual,” he began.

“You said you were open to alternative writing styles.”

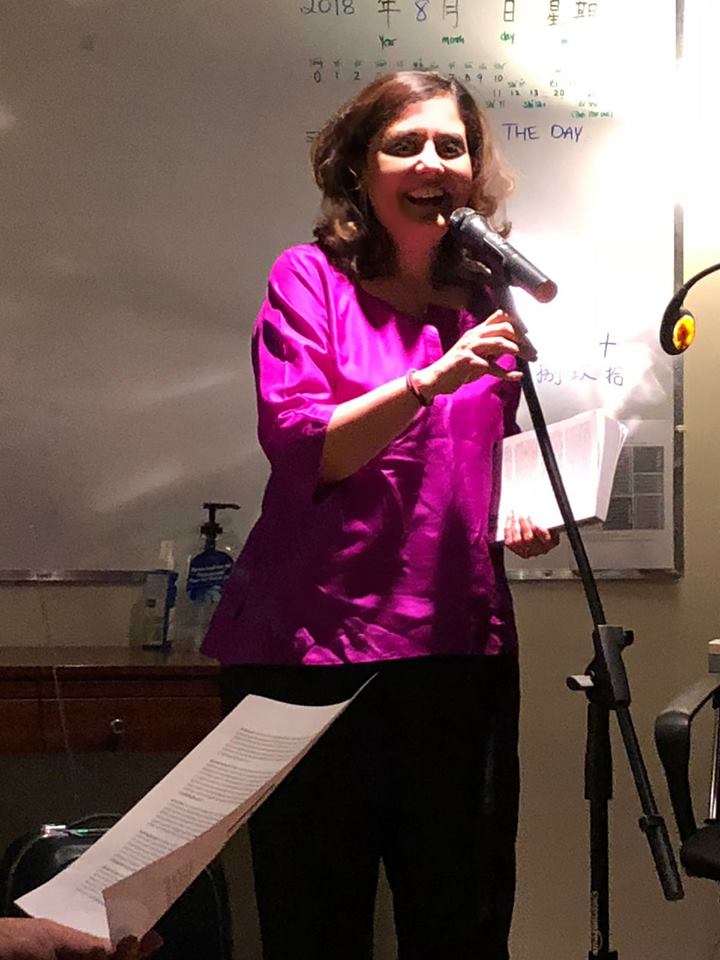

He nodded and then he said something that I’ve quoted many times when speaking at book events; he said, “Maria, you have a flair for creative writing. You should take my creative writing course in the fall.”

I said, “Sure.” “It’s called Writing Creative Non-Fiction.”

When I’m feeling anxious and unsure in a new space, I always sit close to the door. I figure that if things get really bad, I can just slip out. When I say slip out, I mean escape. The writing class was at 8 o’clock on a Friday morning, not a time when I’m at my most creative, but when I arrived, the class was almost full. I sat close to the door.

The professor asked us to go around the circle giving our names, our majors, and our writing goals. He looked at me but then nodded to the student who was sitting beside me, “Let’s start with you. And go this way.”

I was terribly relieved when I saw that all the other students would speak before I would – it would give me a chance to relax before I had to speak, and really, how hard was it to give your name, major, and goal?

I forgot the students’ names almost instantly but their goals were impossible to forget. They said things like, “Hi, I’m majoring in Creative Writing, of course, and studying to be a playwright.” Others specified, journalist, novelist, screenwriter, poet. All creative writing majors. When it was my turn, I looked toward the door but of course, I’d left it too late to escape.

I said, “I’m Maria Coletta McLean. I have a double major in English Literature and Women’s Studies and my plan is to apply to the Faculty of Education after graduation and become a teacher.”

My statement was followed by a brief silence before the professor announced a coffee break. I was pleased when a friendly classmate approached me.

“Can I ask you a question?”

Others lingered behind him within hearing range. I was thinking he was going to ask me to come with them to get a coffee.

He said, “How’d you get into this class?”

The student wasn’t sarcastic or aggressive, just puzzled. The others leaned in.

“The professor suggested I take the class,” I said.

They looked at each other.

One of them said, “You must have had a great portfolio.”

“What’s a portfolio?”

At first, it sounded simple enough: our assignment was to write two pages about our own life every week and hand them into the professor for comments and grading. Two pages seemed like a lot because I considered my life to be pretty ordinary and who wants to read ordinary? But I figured I could do it.

At first, it sounded simple enough: our assignment was to write two pages about our own life every week and hand them into the professor for comments and grading. Two pages seemed like a lot because I considered my life to be pretty ordinary and who wants to read ordinary? But I figured I could do it.

The second part of the assignment was more complicated and infinitely more frightening. Each week, selected students would read their work aloud to the class and the class, as well as the professor, would comment on it. The professor made it very clear that we were to, “Leave any negativity at the door,” which I’m sure was meant to sound encouraging but I immediately heard voices in my head, and they were saying things like, “How’d you get into this class?” “Why do you think anyone would be interested in your ordinary, a.k.a. boring, life?”

Plus the garbage can was right beside the door and somehow that seemed like a bad omen, an invitation for someone to say,

“What you’ve written is complete rubbish. Chuck it.”

The others all signed up eagerly to read their writing aloud and to hear our comments. I was mostly silent for the first few weeks partly because I was uncertain about how to comment and wanted to hear a few responses before attempting any of my own and partly because some of the writing was pretty obscure, at least to me. What were they writing about?

I was beginning to get the hang of positive, constructive criticism, and then the professor said, “Maria, you haven’t had a chance to read your work aloud yet. Shall we put you down for next week?”

I couldn’t avoid sharing my work with others any longer. It was time to step up. To be brave.

Others had written stories about their childhood but I didn’t feel I could write about mine. I’d had a happy childhood; I’d grown up in a warm, protective, nuclear family within a large extended family. I thought most people had the same experience but I was learning from the other students’ stories that not all childhoods were happy, plus happiness didn’t make a good story unless it was shattered by divorce or death or some other catastrophe.

I decided to write about the night my father got lost walking home from the Senior’s Centre and my husband Bob and I found him standing in the middle of a dark street, unsure which way to turn. And when I approached my father, he explained that he couldn’t find his house and when I explained that he was on Church St but he lived on King St, he said, “Thank you,” as if I were a stranger because he didn’t know who I was.

He didn’t know who I was.

It was a tough story to write but my professor had this expression that he liked to use, “Only emotion endures.”

I thought this story qualified.

If it was difficult to write, it was even harder to read aloud and then to hear silence. I kept my head down; a teardrop fell on my desk. Finally, the professor said, “Sometimes there’s nothing to say about a story except that it’s well-written, and that’s the case here. Any other comments?”

One student said he’d like to read more about my father and I held onto that one comment and began to write my father’s stories, two pages a week, over the rest of the semester.

Our final assignment in creative writing class was to research and follow the submission process and then to submit a piece of writing – any genre, any topic, any publication. I recognized this assignment as a chance for us to experience rejection because our professor had another favourite saying, “Sometimes a published writer is the only writer left standing after everyone else has given up and gone home.”

Many of the students had submitted to literary magazines, which I knew nothing about, or to publishing houses if they already had a book manuscript. All I had was the experience of writing two pages a week; I didn’t read literary magazines; I was nowhere near a manuscript.

Aside from my required university reading all I was reading with any regularity was The Toronto Star newspaper. There was a column in the first section of the newspaper that welcomed submissions from readers. They required short personal pieces on any topic. The column was called, Have Your Say, and it was part of the op-ed page. I followed the guidelines carefully and mailed off my submission – those were the days before everything was done online – and I watched for the mail. Nothing came.

The phone rang and Bob covered the receiver and said to me, “It’s a woman calling from The Toronto Star.”

“We already subscribe to The Star,” I said.

And Bob shook his head, and handed me the phone. The op-ed editor said she loved my piece and would publish it the following week and I’d receive a cheque in the mail, and best of all, she asked if I had anything else to submit.

In retrospect, I understand that the piece I’d sent to The Star was pretty raw and rather controversial, and a little inflammatory. It was about the stupid, thoughtless and absolutely useless things people had said to me at my father’s funeral. And my reaction to those comments: anger, anger, and more anger, which had to be buried by the necessity to be polite, to be grateful for their presence, to say the right thing even though I thought of many inappropriate responses.

I didn’t know at the time that anger is a form of grief and to be honest, I didn’t care about stages of grief or alternative expressions of grief; I only cared about the fact that my father was dead. I couldn’t get past a fact that I had no power to change: my father was dead, my father was dead, my father was dead, and I didn’t want to discuss the beautiful floral arrangements or the weak coffee or listen to others’ experience with death.

I didn’t realize that the piece would affect people so strongly. Even though I didn’t use names, it didn’t matter because many of my friends, neighbours, and relatives were sure that I was writing about them, and what they’d said or done. They felt they’d been misunderstood, misquoted, judged harshly; they felt they’d been included in my story, or worse, excluded from my story. I listened to angry phone calls and I learned to repeat the phrase, “I’m sorry to hear that,” over and over again. I discussed it with my writing professor. He said, “It’s not worth writing if you’re not going to be honest.”

I began to research how to get published. I did not do this in an acceptable prescribed manner because I had no idea that this method existed. I did this by taking books off my shelf that I had enjoyed reading and looking inside the front cover to see who the publisher was. I sent a letter and a few pages of my writing to my list of publishers and waited. I didn’t have to wait long: they all sent back rejection letters. Some were form rejection letters that the publisher obviously sent to everyone, who thought they were a writer, and a few responses were personal letters commenting on the writing: they all wished me well. Well, what to do? I read an article about literary agents that said agents already had a working relationship with editors at different publishing houses and agents knew which editors would be interested in different genres. So instead of submitting, reading rejection letters, resubmitting, I thought I’d take the agent route. Let someone else do that job.

I began to research how to get published. I did not do this in an acceptable prescribed manner because I had no idea that this method existed. I did this by taking books off my shelf that I had enjoyed reading and looking inside the front cover to see who the publisher was. I sent a letter and a few pages of my writing to my list of publishers and waited. I didn’t have to wait long: they all sent back rejection letters. Some were form rejection letters that the publisher obviously sent to everyone, who thought they were a writer, and a few responses were personal letters commenting on the writing: they all wished me well. Well, what to do? I read an article about literary agents that said agents already had a working relationship with editors at different publishing houses and agents knew which editors would be interested in different genres. So instead of submitting, reading rejection letters, resubmitting, I thought I’d take the agent route. Let someone else do that job.

I sent out letters and a few pages of the book to agents and waited: I had some rejection letters, a lot of silence, and then a phone call from an agent who was at the Toronto airport waiting to board a flight to London for the London Book Fair. She said she’d read my pages with pleasure and wanted to see the rest of the book. I sent it out the next day even though she wouldn’t be back in her Vancouver office for two weeks: I wanted the manuscript to be there waiting for her.

This was not the beginning of a happily ever after moment, even though I signed a contract with the agent, it was the beginning of a two-year wait while my agent submitted my manuscript to one editor or another, to one publisher to another, and reported back that everyone had rejected it. So, I learned that it’s hard to survive as a writer if you don’t have another source of income. But I kept on writing even though it seemed that no one wanted to publish my work. It’s a truly dedicated writer or a truly delusional one who is willing to do this.

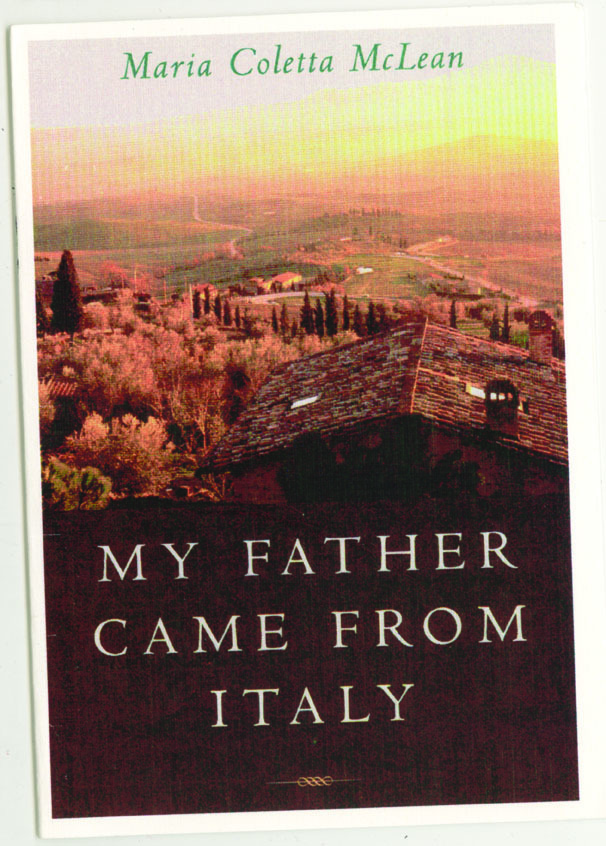

My Father Came From Italy was published by Raincoast Books in the year 2000.

My Father Came From Italy was published by Raincoast Books in the year 2000.

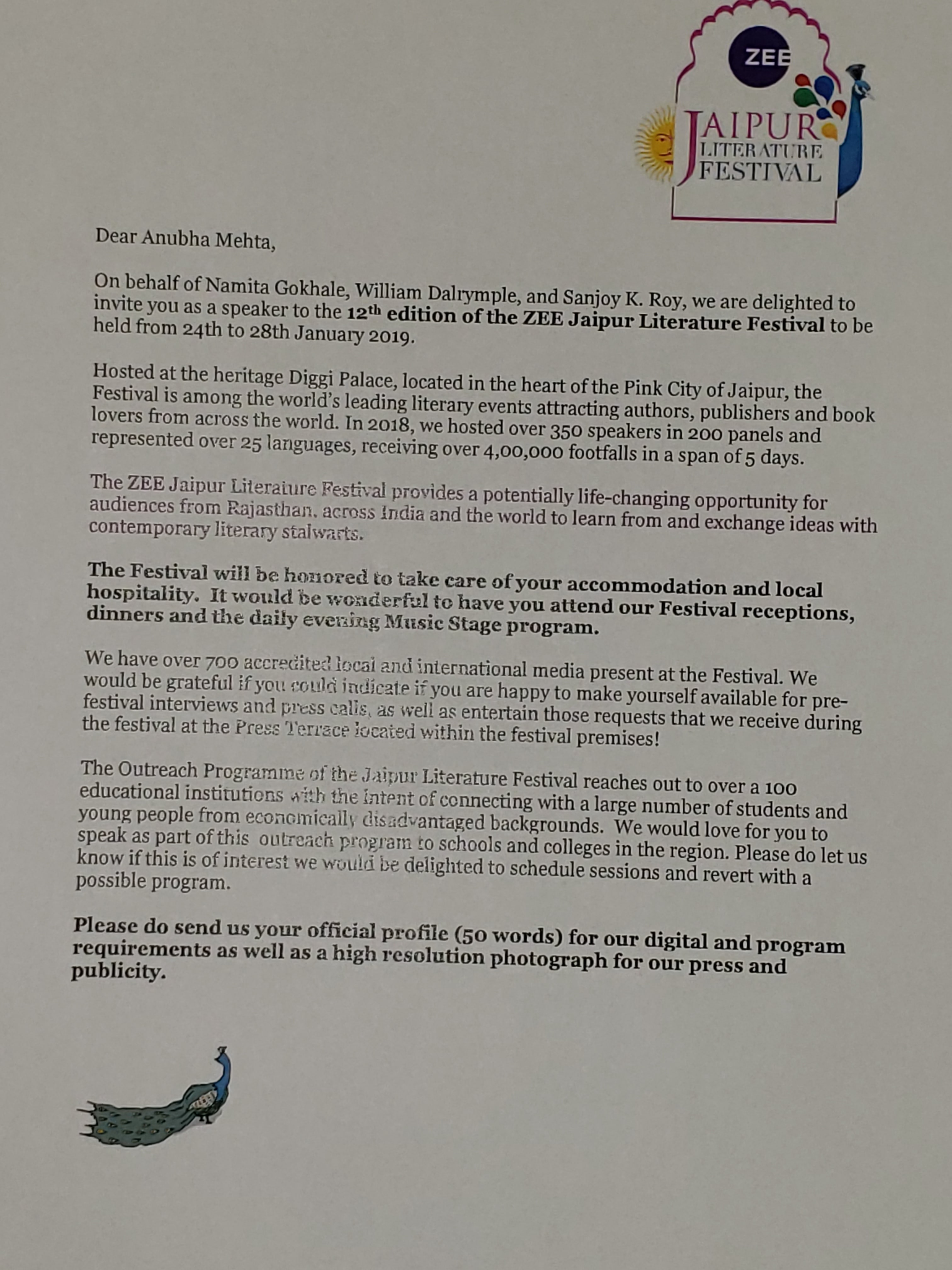

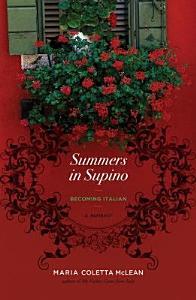

Summers in Supino: Becoming Italian was published by ECW Press in 2013. Privacy is a Foreign Word in Supino will be published by Inanna Publications in 2022. Meanwhile, I’m still writing.

Summers in Supino: Becoming Italian was published by ECW Press in 2013. Privacy is a Foreign Word in Supino will be published by Inanna Publications in 2022. Meanwhile, I’m still writing.

I welcome your comments. All comments are moderated so may not show up immediately. But I will surely get back to you. You can also contact me if you are interested in contributing to my blog, ‘Tell-Tale’ I look forward to hearing from you.