An Interview with Award-Winning Author: Mariam Pirbhai on Her Life, Thoughts, and Journey in Canada

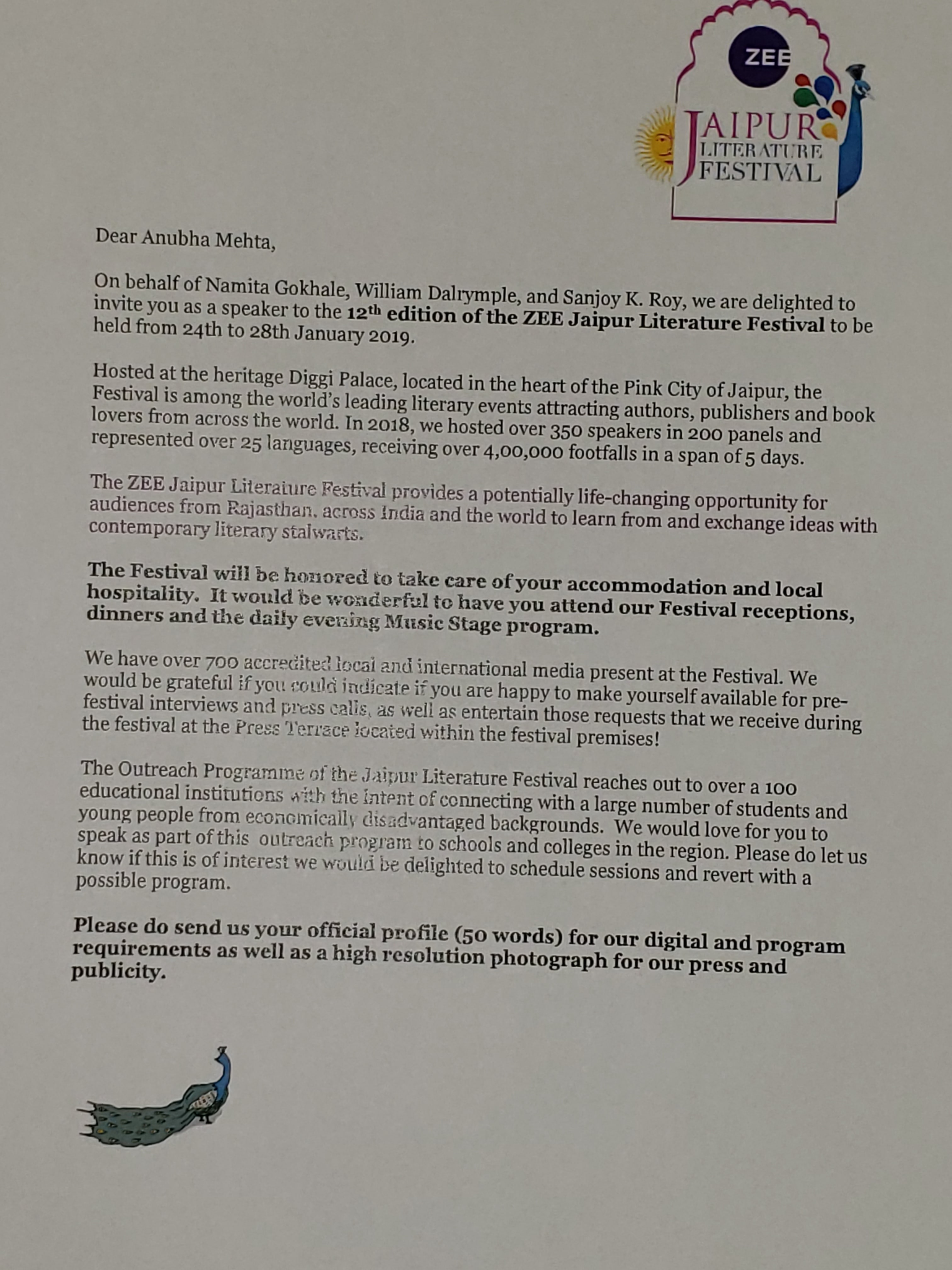

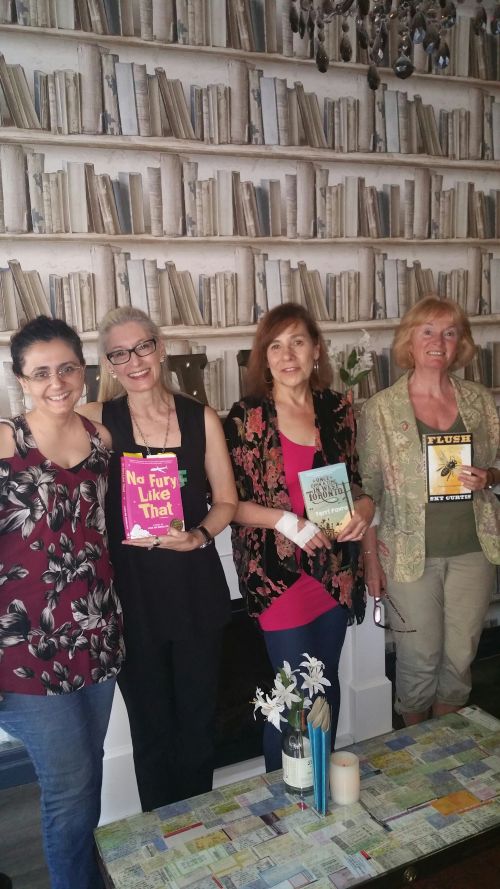

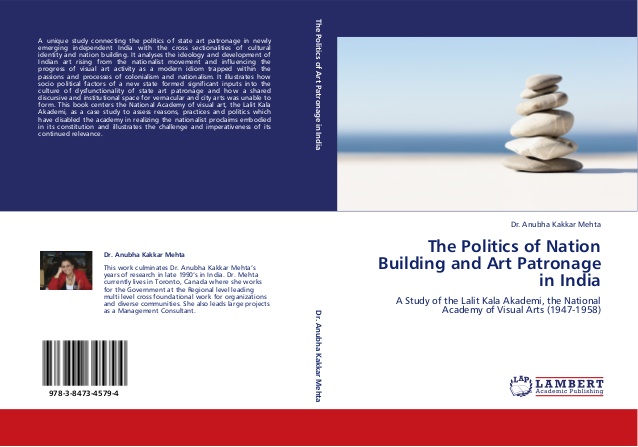

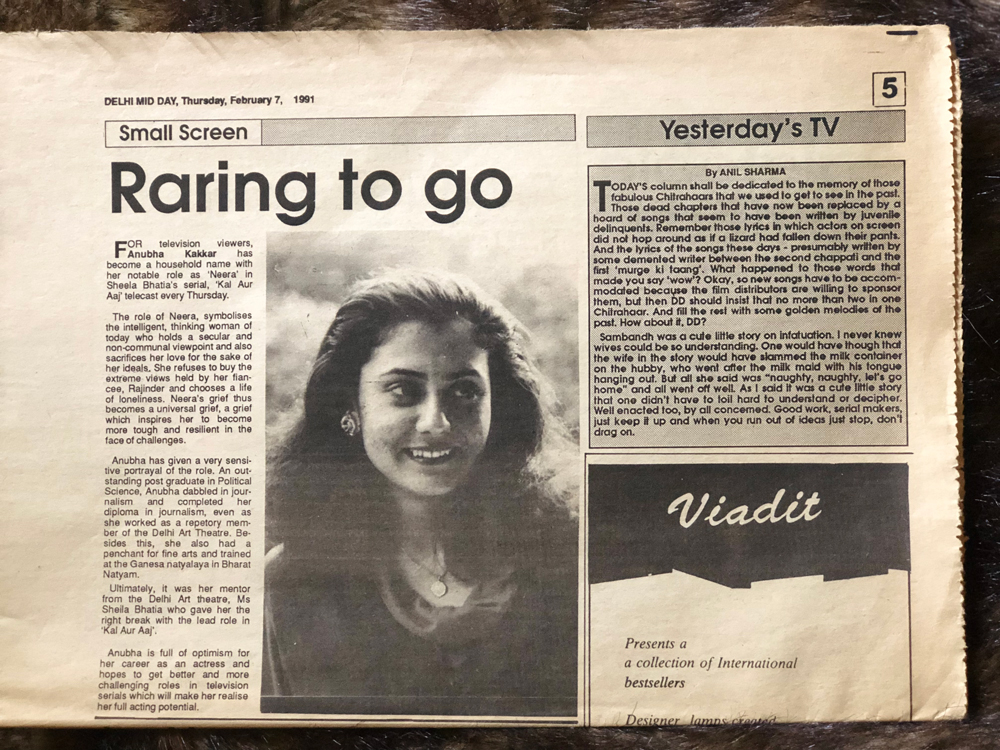

Interviewed by: Anubha Mehta

Mariam Pirbhai was born in Pakistan and lived in England and the Philippines before her family immigrated to Canada. She is the author of a debut short story collection titled Outside People and Other Stories, and numerous academic studies on the kinds of literature and cultures of the South Asian diaspora. She is a Professor in the Department of English and Film Studies at Wilfrid Laurier University, where she teaches and researches in the area of postcolonial studies and global Anglophone literatures. She and her husband live and work in Waterloo, Ontario.

Anubha: When did you arrive in Canada and what were your first impressions?

Mariam: I arrived in Canada with my family, when I was seventeen years old. We landed in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

My first impression of this country was the apparent wealth of the general population; the cleanliness of the place; the variety of choice for consumers; the vast, expansive landscape and the cold, even in June, when my family arrived here!

Anubha: In the initial settlement years, what did you have the most difficulty with?

Mariam: While I was excited about the prospect of starting my university degree immediately, the transition into a new system in a new country, new continent, new everything–with no support in the sense that my parents were also newcomers who had no knowledge of the system much less a university education–this was a major challenge which definitely impacted my early years of settlement and acculturation. If there were services at the university or elsewhere to help with these transitions, I was not aware of them. I think our assumption was that it was up to us to figure things out on our own. Sink or swim was our attitude, I suppose—a sadly ironic motto for new immigrants.

Anubha: Over the years what impact has Canada had on your life and goals?

Mariam: The principles of equality and social justice that are central to this country’s tenets as a social democracy. (Without suggesting that this is a utopia, of course.) My childhood values of education, cultural openness, empathy continue to be major values, which hopefully also inform my own contributions as a Canadian.

Anubha: Have your experiences of a life in another country helped or hindered you in settling here?

Mariam: Living in another country shakes the very core of our beings. We often find ourselves in a place without any established connections, be they in the form of friendships or family, or wider networks of support. It becomes a kind of rebirth but without the nurturing factor, or the sense of security that comes with familiarity. We have to start over on every level, much of the time without any kind of financial or other cushions. Anyone of these experiences forces upon us a reality that essentially strips us bare, where nothing can be taken for granted anymore. If this is not a life lesson of resilience and self-preparedness, I don’t know what is.

Anubha: What are your views on Canada’s Diversity and Freedom?

Mariam: While I could make a blanket statement and say that Canada permits greater liberties (e.g., for women, in terms of sexual diversity and freedoms, in terms of regulated and humane labour laws, safety and security, etc.) than one might find in many others parts of the world, I also understand that we live in a world of “relative” freedoms.

This society (Canada) has arrived at many of these liberties through centuries of colonization–capitalizing on the resources, human labour, cultural capital and knowledge systems of the non-western world. Colonization has shackled—violently and militantly so–much of the non-western world to political and international bodies, as well as intellectual and ideological systems of thought that consistently deracinate and disempower, while disavowing these societies’ right to political and social autonomy. The so-called freedoms of this society have, in other words, arrived at a hefty price to the rest of the world. And the irony that millions now flock to Canada for the very same freedoms that they have been stripped of through five hundred years of colonization and ongoing systems, largely neo-imperial, of economic, ideological and sociopolitical hegemony, is not lost on most of us from the “former colonies.”

This is not to suggest that we are not also responsible for our own destinies, no matter where we are from, but I find this to be one of those questions that set up false and problematic dichotomies which we, as immigrants, are almost expected to subscribe to. I also hesitate to make such comparisons (that is, between my place of birth and Canada) because I came here at a young age, and did not have the opportunity to travel back and forth, as transnationals often do, so I cannot speak to these inherent differences as they may stand or as they are unfolding in my country of origin which is, like Canada, a constantly evolving and changing society.

Anubha: What do you most like about your life here?

Mariam: My ability to sit in a doctor’s office and patiently wait my turn alongside both the richest and the poorest member of this society (though of course the increasingly two-tiered healthcare system and forms of medical tourism are fast corroding such things). My understanding that there is a judicial system that can be relied on, at least for most of my civil liberties. These are some of the fundamentals of life here that I value deeply.

What is the one thing you would change in society?

Mariam: Perhaps not so much change but continue to challenge, in my research, scholarship, teaching and, to some extent, my creative writing, its sense of self-righteousness and paternalism, particularly when it comes to its self-image on the world’s stage, which I believe continues to be grounded in an old colonial Salvationist mythology of the West as the moral and social police of the world.

As a post-colonialist (or scholar of colonial and postcolonial literatures and history), I can’t help but see things through this trans-historical filter, where the past is always present. Canada has simply not reckoned enough with its past or with its current forms of imperialism.

Now, as immigrants, we all live here and are part of both the positive and negative aspects of this society, whether it be in the form of its systemic structures of inequality, in our own position as a new wave of “occupiers” of indigenous lands, in our subscription to certain cultural, historical and national myths, or as part of larger global systems of inequality. This means we also have the potential to be part of the collective will and consciousness that pushes for awareness, reckoning, change.

If you could change one thing in the past what would that be?

As the daughter of immigrants, I think I might not be alone in wanting to turn back time just enough to tell my mother—and perhaps both my parents–how much more I understand and appreciate the strength, creativity and resilience with which they had to face some of the hardest of life’s challenges, particularly as they were further compounded by immigration and displacement.

Points to Ponder for Our Readers:

I look to challenges as an opportunity for growth and this as a central axiom of my life. So far it has worked well for me. I believe in being accountable for one’s choices. If I make changes it will not be through regret or dissatisfaction, but rather for the sake of renewal, regeneration, and the desire to look forward to all that this short life has to offer in terms of individual potential and human potential. When you are faced with challenges , do you find that they are opportunities for growth?

1 Comment

We are defined by our attitude towards life. Our life takes a turn depending upon whether we see a challenge as a hurdle or an opportunity to strive better. An interesting point to Ponder.

I welcome your comments. All comments are moderated so may not show up immediately. But I will surely get back to you. You can also contact me if you are interested in contributing to my blog, ‘Tell-Tale’ I look forward to hearing from you.